Auktion Nr. 164

„Wolbeck“ – Sammlung Römischer Münzen (Lose 1-357)

Das Live bidding startet am 15. März 2026 ab 17:00 Uhr

UND

Auktion Nr. 165

Antike und moderne Münzen (Lose 1-1105)

Das Live bidding startet am 05. April 2026 ab 17:00 Uhr

Every first Sunday of the month is Naumann Sunday

and sometimes there is Special Collection Sunday!

Münzen der Griechen

★ Fantastic Horse Depiction ★

SICILY. Entella. Punic Issues. Tetradrachm (Circa 320/15-300 BC).

Obv: Head of Arethousa left, wearing grain-ear wreath; three dolphins around.

Rev: Head of horse left; palm tree to right.

Jenkins, Punic 250 (O78/R212); CNP 264; HGC 2, 289.

Condition: Good very fine.

Weight: 17.27 g.

Diameter: 26 mm.

Münzen der Griechen

★ Ex Nomos 2012 ★

MACEDON. Akanthos. Tetradrachm (Circa 480-470 BC).

Obv: Lion right, attacking bull crouching left; A above; floral ornament in exergue.

Rev: Quadripartite incuse square.

Desneux -, cf. 90; HGC 3.1, 384.

Ex Nomos 6 (2012), lot 39; ex Nomos 9 (2014), lot 71

Condition: Extremely fine.

Weight: 17.21 g.

Diameter: 29 mm.

Münzen der Griechen

★ Classic Kyzikos Tetradrachm ★

MYSIA. Kyzikos. Tetradrachm (Circa 410-390 BC).

Obv: Head of Kore Soteira left, wearing sphendone covered with a veil; grain-ears in hair.

Rev: KYZIKHNΩN.

Head of lion left, mouth open with tongue protruding; tunny fish below, shell to right.

Pixodarus Type 1; SNG BN 403 var. (symbol); BMC 134.

Condition: Good very fine.

Weight: 14.73 g.

Diameter: 26 mm.

Münzen der Römischen Republik

★ High End Didrachm ★

ANONYMOUS. Didrachm or Quadrigatus (Circa 225-214 BC). Rome.

Obv: Laureate head of Janus.

Rev: Jupiter, holding sceptre and thunderbolt, in quadriga driven by Victory right; ROMA incuse on tablet in exergue.

Crawford 28/3; HN Italy 334; RBW 64.

Condition: Near extremely fine.

Weight: 6.76 g.

Diameter: 23 mm.

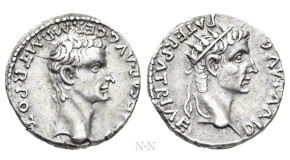

Münzen der Römischen Kaiser

★ Superb Portraits ★

CALIGULA (37-41), with DIVUS AUGUSTUS. Denarius. Lugdunum.

Obv: C CAESAR AVG GERM P M TR POT.

Bare head of Caligula right.

Rev: DIVVS AVG PATER PATRIAE.

Radiate head of Divus Augustus right.

RIC² 10.

Rare.

Condition: Good very fine.

Weight: 4 g.

Diameter: 18 mm.

Münzen der Römischen Kaiser

NERO (54-68). GOLD Aureus. Lugdunum.

Obv: NERO CAESAR AVG IMP.

Bare head right.

Rev: PONTIF MAX TR P X COS IIII P P / EX – SC.

Virtus standing left, foot on enemy’s head, holding spear and balancing parazonium on knee.

RIC² 40; Calicó 437.

Rare.

Ex Dr. Reinhard Fischer 159 (2017), lot 95

Condition: Near very fine.

Weight: 7.2 g.

Diameter: 20 mm.

Münzen der Römischen Kaiser

VESPASIAN (69-79). GOLD Aureus. Rome.

Obv: IMP CAESAR VESPASIANVS AVG.

Laureate head right.

Rev: COS ITER TR POT.

Pax seated left on throne, holding branch and caduceus.

RIC² 28; Calicó 607.

Ex Dr. Reinhard Fischer 168 (2019), lot 38

Condition: Good fine.

Weight: 7.1 g.

Diameter: 20 mm.

Münzen der Römischen Kaiser

★ Ex Auctiones 2014 ★

TRAJAN (98-117). GOLD Aureus. Rome.

Obv: IMP CAES NERVA TRAIAN AVG GERM.

Laureate bust right, wearing aegis.

Rev: P M TR P COS IIII P P.

Hercules standing facing on pedestal, holding club and lion’s skin.

Woytek 99e; RIC 50; Calicó 1053.

Ex Auctiones E-32 (2014), lot 69

Condition: Very fine.

Weight: 7.3 g.

Diameter: 19 mm.

Münzen der Römischen Kaiser

TRAJAN (98-117). Sestertius. Rome.

Obv: IMP CAES NERVAE TRAIANO AVG GER DAC P M TR P COS V P P.

Laureate bust right, slight drapery.

Rev: S P Q R OPTIMO PRINCIPI / S C.

Trajan, thrusting spear at fallen Dacian below, on horse rearing right.

Woytek 317b; RIC 543.

Condition: Extremely fine.

Weight: 27.56 g.

Diameter: 34 mm.

Münzen der Römischen Kaiser

★ „WOLBECK“ SAMMLUNG ★

THEODOSIUS II (402-450). GOLD Solidus. Constantinople.

Obv: D N THEODOSIVS P F AVG.

Helmeted and cuirassed bust facing slightly right, holding spear and shield decorated with horseman motif.

Rev: CONCORDIA AVGG Θ / CONOB.

Constantinopolis seated facing on throne, head right, with foot set upon prow and holding sceptre and globus surmounted by crowning Victory; star to left.

RIC 202; Depeyrot 73/2.

Condition: Extremely fine.

Weight: 4.47 g.

Diameter: 20 mm.

Münzen der Römischen Kaiser

★ „WOLBECK“ SAMMLUNG ★

VALENTINIAN III (425-455). GOLD Solidus. Ravenna.

Obv: D N PLA VALENTINIANVS P F AVG.

Rosette-diademed, draped and cuirassed bust right.

Rev: VICTORIA AVGGG / R – V / COMOB.

Valentinian standing facing, with foot set upon serpentine human head, holding long cross and crowning Victory on globus.

RIC 2018; Ranieri 96; Depeyrot 17/1.

Condition: Good very fine.

Weight: 4.39 g.

Diameter: 21 mm.

Münzen der Römischen Kaiser

★ „WOLBECK“ SAMMLUNG ★

MAGNUS MAXIMUS (383-388). Siliqua. Treveri.

Obv: D N MAG MAXIMVS P F AVG.

Diademed, draped and cuirassed bust right.

Rev: VIRTVS ROMANORVM / TRPS.

Roma seated facing on throne, head left, holding globus and spear.

RIC 84b.1.

Condition: Good very fine.

Weight: 2.15 g.

Diameter: 17 mm.

Newsletter

Mit unserem Newsletter werden Sie stets über Neuigkeiten informiert. Verpassen Sie keine wichtige Nachricht mehr! Tragen Sie dafür nur die E-Mail Adresse ein, an die der Newsletter versendet werden soll. Natürlich können Sie den Newsletter jederzeit wieder abbestellen.

Nach Absenden des Formulars erhalten Sie von uns eine Email zur Bestätigung.